Apologies for the long delay since the last installment. This entry, for Memorial Day, is on memory.

In classical rhetoric, skill in memory was considered essential to good speaking and good citizenship. Memory is one of rhetoric's five parts or "canons" (the others being invention, style, arrangement, and delivery). Memory supplied the speaker with anecdotes, examples, and maxims that could be brought to bear in a variety of situations. It allowed the speaker to connect with his or her audience, bring forth detailed examples, and energize a dry or abstract discussion.

Our current administration does not seem to share this exalted view of memory. Consider the U.S. attorney firing scandal. In his March 2007 testimony to the Senate Judiciary Committee, Kyle Sampson "used the phrase 'I don't remember' a memorable 122 times," according to the Washington Post's Dana Milbank. Alberto Gonzalez couldn't quite match that in his testimony: he only "said 71 times that he either could not recall or did not remember conversations or events." President Bush responded to this attack of amnesia with sympathy, noting that the Attorney General "answered every answer he could possibly answer, honestly answer." Well, if you're only talking about honest answers . . .

What I want to address here is how the administration, for all its forgetting, uses and abuses memory as a central tool of policy.

In the Institutes of Oratory, Book 11, Chapter 2, our old friend Quintilian notes how memory comes and goes:

Most . . . are of opinion that certain impressions are stamped on the mind, as the signets of rings are marked on wax. But I shall not be so credulous as to believe that the memory may be rendered duller or more retentive by the condition of the body. I would rather content myself with expressing my admiration of its powers as they affect the mind, so that by its influence, old ideas, revived after a long interval of forgetfulness, suddenly start up and present themselves to us, not only when we endeavor to recall them, but even of their own accord, not only when we are awake, but even when we are sunk in sleep. This peculiarity is the more wonderful, as even the inferior animals that are thought to lack understanding, remember and recognize things, and however far they may be taken from their usual abodes, they still return to them again. Is it not a surprising inconsistency that what is recent should escape the memory and what is old should retain its place in it? That we should forget what happened yesterday, and yet remember the acts of our childhood? That things should conceal themselves when sought and occur to us unexpectedly? That memory should not always remain with us, but sometimes return after having been lost? (Emphasis added)Memories get classified and categorized in a variety of ways. One type of memory viciously exploited by the Bush administration is the so-called "flashbulb memory." This is the memory (often recalled in vivid detail) of a major traumatic event, sometimes a public one like the Kennedy assasination, the Challenger disaster, or September 11. For a time it was thought that flashbulb memories were quite accurate because the trauma fixed the memory very quickly. More recent research, however, has shown that flashbulb memories change over time. A 2004 study by Weaver and Krug (published in the American Journal of Psychology) examined flashbulb memories of September 11. The authors found that people have high confidence in their 9/11 memories but that memories declined in accuracy over time. What this means is that later surveys found that recollections of September 11 matched less and less with what the subjects reported in the first 48 hours. (The abstract and citation info are here; I can send you a PDF of the whole article if you drop me an email.)

Interestingly, memories of September 11 reported a week or more after the event remained consistent. Weaver and Krug refer to this week-long period as consolidation:

During this consolidation processes [sic], memories are especially malleable. Information can be added to the memories (such as watching the video of the first plane hitting the World Trade Center). Even more likely, details can be lost; recall that at one time on the morning of September 11 there were reports of a car bomb exploding outside Capitol Hill. For most of us, this information is no longer a part of our memories of that morning. Some events whose significance is not apparent at the time occupy a greater role in our memories than they may have occupied during the actual event. Other events that appear to be significant turn out not to be and therefore are discarded. (Weaver and Krug 526)I bring this up because the memory of September 11 is one of the favorite images of the Bush administration. Unlike the Attorney General's memory lapses, Bush's invocations of "the lesson of September 11" are beyond counting. I have no doubt he will invoke it today, Memorial Day 2007. Yet even in this slight shift — from memory to lesson — we see the transformation of image into emblem, of was into ought, of fact into mission.

For President Bush and his enablers, every new death is a memory to be exploited, a confirmation that we should never forget "the lesson of September 11" — even though whatever lesson September 11 offers is a lesson President Bush has never learned.

We must resist this transformation. We must refuse to consolidate the memory of the newly dead in Iraq with the events of September 11.

But does this do any good? In his heartbreaking op-ed in the Washington Post, Andrew J. Bacevich thinks not:

Not for a second did I expect my own efforts to make a difference. But I did nurse the hope that my voice might combine with those of others -- teachers, writers, activists and ordinary folks -- to educate the public about the folly of the course on which the nation has embarked. I hoped that those efforts might produce a political climate conducive to change. I genuinely believed that if the people spoke, our leaders in Washington would listen and respond.(If you haven't read Bacevich's op-ed, please stop now and read it. Come back only when you've stopped shaking.)This, I can now see, was an illusion.

The people have spoken, and nothing of substance has changed. The November 2006 midterm elections signified an unambiguous repudiation of the policies that landed us in our present predicament. But half a year later, the war continues, with no end in sight. Indeed, by sending more troops to Iraq (and by extending the tours of those, like my son, who were already there), Bush has signaled his complete disregard for what was once quaintly referred to as "the will of the people."

For all of us who want to end this war, this past week has been profoundly disappointing. But I think Bacevich sells himself short. All our voices have not (yet) stopped this war. But our voices, added to the memory of this grim time, may help those who come later build a country again.

One of my favorite lines in Apocalypse Now is spoken by the crazed Lt. Col. Kilgore, played by Robert Duvall: "Someday this war's gonna end..." That he does not finish the sentence suggests both that he is happy with perpetual war and that he has no idea how to deal with peace.

Listen folks: Someday this war's gonna end. All our voices together may or may not hasten its ending. But the memory of what we said and did will help us complete that sentence for ourselves and for each other.

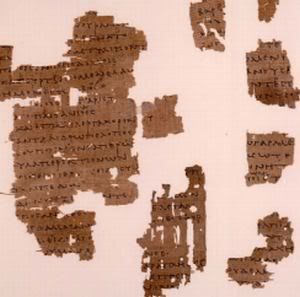

Did you know that the art of memory was invented? Yes, it's true, or so they say: by the Greek poet Simonides of Keos. But get this: the art of memory was invented to investigate the

The invention of this art is fathered upon Simonides; for when the same man (as the fable records) had made in behalf of a triumphant champion called Scopas for a certain sum of money a ballad such as was then wont to be made for conquerors: he was denied a piece of his reward, because he made a digression in his song (which in those days was customarily used) to the praise and commendation of Castor & Pollux (who were then thought being twins, & got by Jupiter to be gods) of whom the champion willed him to ask a portion, because he had so largely set forth their worthy doings. Now it chanced that whereas there was made a great feast to the honor of the same victory, and Simonides had been placed there as a guest, he was suddenly called from the table and told that there was two young men at the door, and both on horseback, which desired most earnestly to speak with him out of hand. But when he came out of the doors, he saw none at all: notwithstanding, he was not so soon out, and his foot on the threshold, but the parlor fell down immediately upon them all that were there, and so crushed their bodies together, and in such sort, that the kinsfolk of those that were dead, coming in, and desirous to bury them every one according to their calling, not only could they not perceive them by their faces, but also they could not discern them by any other mark of any part in all their bodies. Then Simonides well remembering in what place every one of them did sit, told them what every one was, and gave them their kinsfolk's carcasses, so many as were there. Thus the arte was first invented. And yet (though this be but a fable) reason might beat thus much into our heads, that if the like thing had been done, the like remembrance might have been used. For who is he that sees a dozen sit at a table, whom he knows very well, cannot tell after they are all risen, where every one of them did sit before?Let me translate: Simonides gives a poem in praise of Scopas, but wasn't paid fully because Simonides had also praised Castor and Pollux in the same poem. Simonides gets called out of the banquet room by two young men; nobody's there when he checks, but the building collapses right then and kills everybody; the bodies are unrecognizable. Simonides, however, remembers who sat where, and by careful examination, identifies the bodies.

The Bush administration has used memory in precisely the opposite manner: to obscure rather than discover; to create fantasy enemies rather than to locate those who have already attacked. For the Bush administration, it is not only the victims who are unrecognizable; it is also the attackers, who bloat and swell into a phantasmagoria of Muslim evilness.

We must not allow our anguish over this week's vote to blur our memory of what happened. Not all Democrats voted to capitulate; not all Democrats who did are unredeemable otherwise. Let's not consolidate too quickly; let's be subtle and forensic, and let's contribute to the memory we can use to recover.

In ancient rhetoric, memory was an oral art, meant for use in legal and political speech-making and debate. Now, of course, we have memory systems: libraries, archives, and — oh yeah — the internets. Little of what we say or write will affect deliberation today or tomorrow. But someday this war's gonna end. And when that happens, we have to remember what was good about this country, and bring it back.

A small note in conclusion. We don't have many of Simonides's own poems: those we do have are fragmented. One well-known epitaph on a tomb reads: "Stranger, bring the message to the Spartans that here / We remain, obedient to their orders." For me, the power of this poem is the distance between its "we" (the dead who speak it) and "their orders."

Another fragment reads: "Not even the gods fight against necessity." I can imagine every Senator and Representative who voted for a blank check reciting these lines. But they are wrong in two ways: a blank check is not a necessity, and elected officials are not gods.

Comments

I've read a number of versions of this story, and as I understand it, Simonides uses his memory system to identify the dead so that their families can bury them. There’s no indication of murder involved, unless you include Castor and Pollux, and I've never before heard that Simonides used his mnemonic system to identify perpetrators.

Are you by chance conflating the story of Simonides Rhetorica ad Herennium's example mnemonic image prepared for a murder trial? Or have I missed something?

Thanks for that: not nitpicking at all. I'm not sure what caused me to have that particular brain-fart. I've corrected the post accordingly.

DK

In the same vein of false memorializing you focus on, the Bush Administration did not "examine the bodies" of 9-11. I would be shocked if any Bush administration official read each obituary that appeared in the New York Times. If they had, they would have seen the real multicultural America that had been attacked.

Anyway, thanks for your insightful reading.